We humans are driven to make our mark somehow. Creativity is an intrinsic element of being human. We are excited by the creation of music, drama, literature, art and architecture, they are, ultimately, the core and sometimes the fossils of civilizations. We particularly value those achievements which outlast a single life, and instinctively feel poorer when they are taken from us. Without disregarding the deeply depressing current human catastrophe of the Middle East, the destruction of ancient archaeological sites in Syria and our reaction to the devastation points to an enduring notion of how we value our ancestors' ability to speak to us through the things they made.

Physically, too, we have evolved to make things. Our marvellous opposable thumb is served by an amazing brain that enables us to realise our ideas through our hands. Our distant ancestors made things all the time; skill to explore and exploit materials was essential to survival, and then became a way to express and record our interventions and sense of world order. Although social structures seem to have divided makers into the most lowly and the most revered people, in different times and places, expertise in making has always had value.

In fact, it's not just our distant forebears who were familiar with tools and materials in an everyday sense. Some of our parents and grandparents made shelves, clothes, garden swings; mended cars, agricultural machinery and made preserves, often from necessity rather than to fill free time. I was mildy shocked to hear recently that only a small minority these days knows how to wire a plug.

As advancing and cheaper technology takes the making of things further from individuals, it takes away some sense of everyday purpose, and maybe connectedness with our physical world. The virtual world swims around our heads. Shopping from a keyboard is, it turns out, not really a substitute for holding an object with a known, perhaps personal, history. Dad's toolbox, Granny's pincushion: bought stuff often just doesn't carry the same emotional charge. Similarly, pinging off emails can only go so far. What's to show for it at the end of the day?

Perhaps the nostalgia laden interiors of ye olde country pubs are just that: a rose tinted view. Life was undeniably harder for great grandad, but those folksy ornaments do illustrate the way we yearn for the days when expert making skills were seen daily in plain view, and universally understood.

The Beeb's Bake Off, of course, feeds off our yearning to get our hands dirty again, to make stuff, and the Pottery Throwdown too. Like many involved in pottery in a serious way, I have mixed feelings about a telly programme which often trivialises and even misrepresents our craft at the service of arbitrarily imposed timescales and 'entertainment' value. Still, it has struck a chord with many who feel the need to reconnect hand, eye and brain, and to experience firsthand the satisfaction of making, and on balance a second series is a Good Thing.

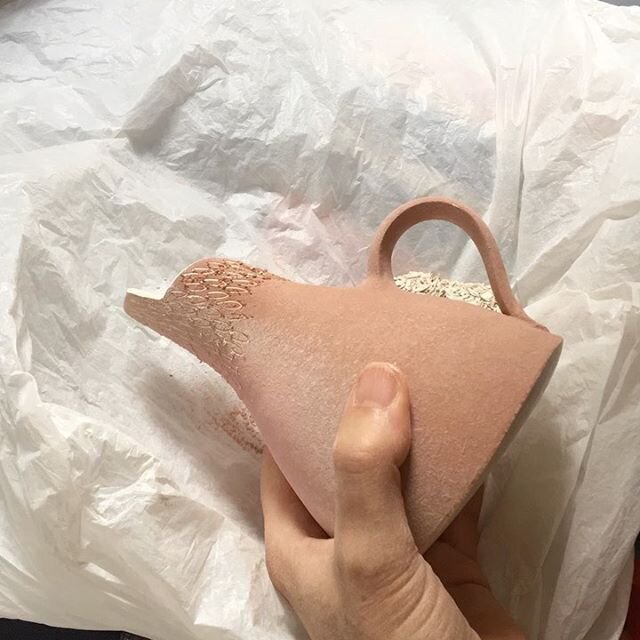

Any creative activity is rewarding; the immediacy of forming responsive clay particularly so. As I suggested earlier, our hands and brains have evolved to support our long-ago urge to find out what materials can do. The ability to use a material well remains psychologically supremely satisfying. A child exploring the possibilities of mud is engrossed, and rediscovering that fascination as an adult is a magical experience.

Clay is better than mud; its potential far greater: it holds its shape; it records impressions; it hardens, can become permanent. I bet I'm not the only potter who still finds that sensation of wet clay in my hands the most compelling, intoxicating, addictive thing. Seeing a potter's thumbprint left on an ancient shard shrinks time to nothing. We are still connected.

Tell Halaf pottery jar, Syria, 5th millennium BC